Since the beginning of COVID, many people have left their jobs. Journalists have described this phenomenon as the “Great Resignation”.

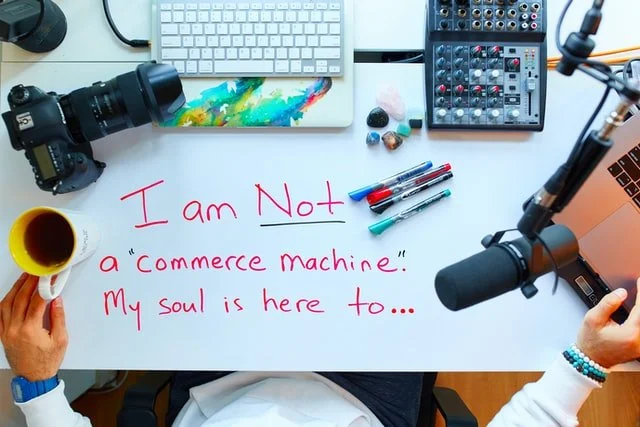

But people are not only resigning from their jobs. They seem to be abandoning the idea that work is just about the paycheck and the perks– that work that doesn’t serve a larger purpose is actually worth doing.

In this post, Jane Rubin, PhD., talks about how therapy can help you navigate this new landscape. By helping patients overcome emptiness, disappointment, and cynicism, Dr. Rubin helps them find the meaning and direction they’re seeking.

Why are people asking these questions about purpose and direction now?

I read an interesting article recently that said that, once people were working at home because of COVID, they were able to see more clearly what their work was really like. Without the proverbial water cooler conversations with co-workers, and without the perks, their actual jobs were not really interesting or fulfilling. I don’t know if that’s how a lot of people felt who left their jobs, but COVID certainly seems to have been the catalyst for a major reappraisal of the role of work in our lives.

What do these people really want?

Many people I’ve talked to feel that they’re missing a larger sense of purpose in their lives. Being good at their jobs, and getting recognition for their work, hasn’t been enough to sustain them through these difficult times. They want to feel that they’re making a contribution to the world and not just to their company’s bottom line.

What does filling that need look like for these people?

The people I work with who do have a sense of purpose believe that what they do has meaning beyond themselves. For example, scientists I talk with love doing science, but what ultimately motivates them is their belief that their research will benefit other people. Writers express a personal love of the creative process, but also feel that their work enriches their readers’ understanding of the world. Grocery store workers feel that their work has helped to sustain their communities through the pandemic.

This sense of a greater purpose helps people successfully deal with work-related frustrations like stalled experiments, writer's block, or customers’ refusals to wear masks. My sense is that, for many people who don’t feel that their work serves a larger purpose, these frustrations became too much to deal with when they were also dealing with the frustrations of COVID.

When the decision to resign happens, what happens next for those seeking their purpose?

I think people who are seeking their purpose fall into two general categories. Some people have experienced a sense of purpose in other jobs, in volunteer work, or in being active members of their communities. When they leave unfulfilling jobs, these people have at least some sense of what they’re looking for.

Some people, on the other hand, have a vague sense that they want something more, but they don’t have a clear idea of what that would look like. In my experience, that’s often because they haven’t had the experience of what the psychoanalyst Heinz Kohut called “idealization”.

Kohut thought that early experiences of being held by our caregivers, of being calmed and soothed by them, form the foundation in later life for being able to devote ourselves to something larger than ourselves. Many people lacked these experiences in their early lives. Their caregivers may have been too anxious or depressed or preoccupied to contain their children’s anxieties. Often, these people are quite cynical about the causes that other people devote themselves to. They protect themselves from disappointment by not allowing themselves to commit themselves to anything.

What does a patient seeking to resolve that insecurity and negativity do?

One thing therapists try to do is create an atmosphere of safety for our patients. Creating that atmosphere involves being very sensitive to the ways in which our patients feel unsafe. If we can give our patients the feeling of being understood, over time they begin to trust us and trust the therapy process. This is only one element in giving people the confidence that they can find and devote themselves to something meaningful, but it’s an important one. If people can have this experience in therapy, they can transfer these feelings to other activities and relationships, and find a greater sense of purpose and direction in their lives.

Are you struggling with finding your purpose? Please reach out to Jane Rubin, Ph.D. Jane Rubin, Ph.D. She is a clinical psychologist in Berkeley, California. She works with individuals in Berkeley, Oakland, the East Bay, and the greater San Francisco Bay Area who are struggling with depression and anxiety. She also specializes in working with people who are trying to find meaning and direction in their lives.